My Ulcerative Colitis Diagnosis: Bayesianism and Eliminative Abduction

My diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was based on clinical history, colonoscopy, CT scan findings, and response to treatment; histopathology was equivocal.

When I see a bird that walks like a duck and swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.

—James Whitcomb Riley (1849–1916)

I was given a presumptive diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC) on March 9, 2018. In this blog post, I recount the symptoms and events that led to this diagnosis.

I was experiencing a few symptoms when I presented to my gastroenterologist (Dr TKF). I remember the date well – February 14, 2018.

It was the last day before the doctor’s clinic closed for the Chinese New Year period, a big deal in these parts. As much as I loathe going to hospitals as a patient (versus as a consultant), I counted myself lucky to have made an appointment to see my gastroenterologist, who has a busy practice, with less than 24 hours’ notice.

If I hadn’t seen him on February 14, 2018, I would have had to wait till his clinic reopened after the Chinese New Year break, i.e., six days. I’m aware, in many places, that a wait of six days for an appointment with a specialist physician would be acceptable, if not good.

In my case, I had already put off seeing him for months (which, in retrospect, was reckless). By the time I called the clinic (late afternoon of February 14, 2020), things had, at least to my mind, become severe enough to warrant an urgent expert opinion.

By the time I saw him on February 14, 2018, my gastroenterologist and I had known each other for about 12 years. We first met at Singapore’s National University Hospital (NUH). I saw him for a diagnostic conundrum a few others in town had trouble solving. He diagnosed idiopathic gastroparesis and recommended treatment that yielded beneficial effects.

Shortly after our first meeting, he joined the hospital where I worked, so we were colleagues until I left the hospital and started my own consulting business in 2009. This prior relationship was meaningful. I trusted his clinical acumen, and he knew about some of my obsessive and compulsive traits. For example, he knew he needed to eliminate colon cancer from the differential diagnosis, or else I’d “keep thinking about cancer” – his words, not mine.

Main Presenting Complaints and History

The chief complaints that made me seek medical help were gastrointestinal. I’ll describe them below – these were the symptoms that I first reported to my gastroenterologist. There were others (which I’ll also detail), but these either (A) did not seem to be relevant initially or (B) escaped my attention until I learned the results of the colonoscopy.

- Irregular bowel movements. The chief complaints that made me seek medical help were gastrointestinal. I’ll describe them below – these were the symptoms that I first reported to my gastroenterologist. There were others (which I’ll also detail), but these either (A) did not seem to be relevant initially or (B) simply escaped my attention until I learned the results of the colonoscopy.

- Left-sided abdominal pain. I had colicky pain on the left side of my abdomen, which could get quite severe, up to 7/10 on the Numerical Rating Pain Scale, usually occurring around bedtime, i.e., between 12 midnight and 2 a.m. The pain would last for a couple of hours and subside spontaneously. It would often be troublesome enough to prevent me from sleeping while I felt the pain. Lying on my left side lessened the severity of the pain, but not the episode’s duration. I’m still unsure of the source of the pain: UC (less likely) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (more likely).

- Rectal (PR) Bleeding. From around mid-November 2017, I noticed intermittent rectal bleeding – bright blood, often mixed with blood clots. The bleeding looked different from hemorrhoid bleeding, which I’ve experienced occasionally since 20.

- Decreased stool caliber. For at least three months, I had noticed a reduction in the caliber of my stools. My understanding was that stool caliber was a non-specific symptom. But with my other symptoms, I thought it could have been significant and reported it to the doctor during our February 14, 2018 appointment.

These symptoms were noticeably worsening over the weeks leading up to my clinic visit. The final straw was experiencing explosive bloody diarrhea and left-sided abdominal pain simultaneously on the afternoon of February 13, 2018. That I had experienced pain during daylight hours was unusual. But I also had not previously experienced the left-sided abdominal pain while sitting on the throne plus having explosive diarrhea. It was time to get professional expert help, hence the phone call to my gastroenterologist’s clinic to make the appointment.

Other Symptoms Probably Related to Ulcerative Colitis

I had other symptoms, which I now believe were likely to have been associated with UC. Around the time I was diagnosed with UC, I had had these symptoms for a prolonged time (measured in years or decades), so the association wasn’t apparent then.

- Pus and mucus on stools. I had observed pus and mucus consistently on my stools for several months. I had seen something similar in the past, but only on rare occasions. It was only after the colonoscopy on February 20, 2018 (see below for more details) and upon direct questioning by the gastroenterologist that I realized the significance of the pus and mucus.

- Rectal pain during defecation. Sometimes, I would experience a sharp, severe pain in my rectum (not my anus) upon defecation. The correct medical jargon for this symptom is odynochezia. I didn’t have it every time I opened my bowels, and it was pretty unpredictable. I didn’t identify any antecedent factors.

- Anal pain. Closer to my initial clinic appointment for my bowel problems, I noticed my anus felt warm/hot all the time. I never tried touching my anus to confirm it was warm/hot, but the sensation in the anus gave the impression it was burning. Initially, I thought it might have been temporary inflammation of my external hemorrhoids, a problem I had known about since I was 20. What made this different from previous episodes in which my hemorrhoids played up was the nature of the pain (constant burning versus a localized “itch” of a thrombosed external hemorrhoid). It never seemed to subside, even after a couple of weeks. This sensation would last a further three weeks after commencement of treatment for UC before it went away for good.

- Fatigue. I had suffered from fatigue for several years, particularly upon returning from work trips out of town. These “expeditions,” which usually last about a week and no longer than a month at a time, really drained me of my energy, which I felt only upon my return home. Often, I lay on the sofa for most of the day, usually doing nothing productive at all. The debilitating fatigue I went through on those occasions, which happened at least monthly (partly because I was traveling at least that frequently), usually lasted 4–5 days. During those years, I just brushed off my fatigue with different excuses: giving 110% for my clients on my expeditions, insufficient sleep on the road, less than ideal diet (e.g., a combination of airport, airline, and fast food), a side effect of aging, stress from being in a foreign environment, etc. My wife used to liken my need for recovery time to the downtime artists take after a tour. There might have been an element of truth in that hypothesis. Still, it doesn’t explain those periods of fatigue that occurred out of the blue when I was working out from my office only and not doing any special performance in the form of a talk, workshop, or on-site visit to a hospital 7000 kilometers from home. Paradoxically, I have never experienced fatigue during any of my assignments. Right from Day 1 of my consulting business, I have always felt excited and energetic while on the job. It didn’t matter where I was on the planet, what the assignment was (from a 1-hour speaking engagement to a 2-day workshop to a 25-day expedition in the heart of South Asia), or how busy my calendar was. The adrenaline rush from the consulting/coaching/training assignments and the determination to provide maximum value to my clients kept me going strong! But afterward, I would need convalescence time, up to a week for business trips and perhaps only a day or two for 1-day speaking/training events. When I experienced fatigue without an obvious trigger (such as out-of-town travel or speaking engagement), I might need between a few days and a couple of weeks to regain my energy and motivation.

- Diminished exercise tolerance. I was fit in my teens and early twenties. I engaged in competitive sports – tennis and swimming – without little trouble. In my late teens, I could run 13 kilometers in about 60 minutes, immediately followed by 30 minutes of resistance training at home and then a 1000-meter swim in the nearby public swimming pool – all this in one evening, at least five times per week for at least two consecutive years. I’d say that was when I was at my fittest. However, something strange happened after about the age of 22. Since then, on innumerable occasions, I have tried to embark on a regular exercise routine several times over the years but could never sustain it for more than a month. I’d give up because of physical injury (e.g., manifesting as back pain), wheezing on mild exertion, or a prolonged perceived fatigue. Each time this happened, I gave myself time to “recover,” and I’d try again, the interval between attempts ranging from months to three years. I never regained the level of fitness of my late teens.

- Low back pain. Low back pain had troubled me for over two decades. I first sought medical help when I was around 24. I received physiotherapy for a few weeks, but that helped little. Over the years, the back pain has waxed and waned spontaneously, sometimes exacerbated by physical activity. There have been some notable episodes in which it was severe, once requiring hospital admission in 2007. An MRI showed degenerative changes and early signs of fusion of the lumbar vertebrae. As correctly pointed out by a friend (Dr RS), my low back pain could have been referred from my rectum, sigmoid colon, or descending colon. How this low back pain was related to my proctitis (see below) was indicated by its dramatic improvement after the commencement of specific treatment of UC. I now believe I have spondyloarthropathy, possibly ankylosing spondylitis, associated with UC.

- Bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Another problem I had for more than a decade was the occasional episode of shortness of breath and wheezing. Exercise or certain foods, like some brands of curry powder, sometimes precipitated these instances of presumed airway obstruction, which responded well to inhaled Ventolin.

- I sometimes took a course of oral Prednisolone if the episode was terrible. Like the back pain, this respiratory dysfunction disappeared after I started taking specific medication to treat UC. For this reason, I suspect my obstructive airway disease was a pulmonary manifestation of UC.

Symptoms Probably Not Related to Ulcerative Colitis

Besides the above, I also had other gastrointestinal symptoms, which I think were more related to IBS than UC.

- Abdominal Bloating. I had intermittent episodes of abdominal bloating, probably related to what I ate. Emotional and psychological stress also played a role in (A) whether I would experience bloating and (B) to what degree if I did experience bloating.

- Intermittent Nausea. Nausea and vomiting were my major symptoms when I was diagnosed with idiopathic gastroparesis in 2006. Since then, I’ve had intermittent, spontaneous episodes of nausea and anorexia, usually lasting up to a fortnight. I had some bouts of nausea in the months before my clinic appointment on February 14, 2018, but I don’t think they had any relationship with UC.

Other Pertinent Information

In the months leading up to the clinic visit, my weight was stable – I certainly wasn’t losing weight – and my appetite was unchanged, though I was testing different diets to see if they helped my symptoms. My body mass index (BMI) was about 27.5, so I might have been considered overweight. (![]() Disclaimer: I don’t believe the BMI is a good indicator of my nutritional status or adiposity.)

Disclaimer: I don’t believe the BMI is a good indicator of my nutritional status or adiposity.)

I’m a lifetime non-smoker.

Although I had traveled extensively, especially within Southeast and South Asia, since I started my healthcare consulting firm in 2009, I traveled to reasonably developed locations (e.g., Singapore, Kuala Lumpur) in the previous few months. I was also careful with the food and water I consumed during my expeditions. Therefore, an infectious cause for my woes was unlikely.

Another important point to clarify is my sexual orientation: I’m a straight guy, and I’ve never engaged in homosexual activity. For the record, I have nothing against the LGBT community. I’m just adding this bit to exclude the possibility my medical problems were due to homosexual sexual activity. Examples of the latter include anal sexual intercourse, anal fisting (aka “fist fornication,” “handballing”), and insertion of foreign bodies. These acts may cause some forms of anorectal disease.

I’ve had no radiation treatment.

I have no family history of colorectal cancer.

Physical Examination

Physical examination did not find any abnormality. My gastroenterologist did not perform a digital rectal exam, consistent with local practice.

My Differential Diagnosis

For months, I had considered the possibility of three conditions:

- Diverticulosis. The only real symptom that would support this diagnosis was rectal bleeding. Uncomplicated diverticulosis isn’t usually associated with abdominal pain. Diverticulosis alone could not explain the other symptoms.

- Diverticulitis disease. Before seeing the doctor, I thought I probably had diverticulitis. Bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain suggested this condition. But the location of the pain was not typical of diverticulitis, and the history of my symptoms didn’t quite fit the typical picture for this disease.

- Colon cancer. I’d be lying if I said I did not seriously consider the possibility of cancer, in particular colon cancer. It didn’t help that a non-blood relative in his eighties told me only a couple of months before I visited my gastroenterologist that the only symptom he had from his colon cancer was decreased stool caliber. I was only in my mid-forties with no family history (of colon cancer), and my weight had been stable. These factors seemed to go against the diagnosis of colon cancer.

Provisional Diagnosis and Rationale for Colonoscopy and CT Scan of Abdomen and Pelvis

Based on my story and his physical exam, my gastroenterologist’s provisional, or pre-test, diagnosis was IBS. He told me both gastroparesis and IBS fall under the spectrum of functional gastrointestinal disorders, suggesting that IBS was an extension of my previously diagnosed gastroparesis. It didn’t sound like cancer to him. Because IBS was a diagnosis of exclusion, he recommended a colonoscopy and a CT scan of my abdomen and pelvis. I was ready to undergo these two tests. He didn’t need to convince me that a colonoscopy was justified, but he offered two other indications for it:

- My age was close enough to be 50, the age at which most guidelines recommend starting regular colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in persons with an average risk of CRC. Interestingly, in its 2018 guideline for CRC screening, the American Cancer Society made a “qualified recommendation” to begin screening in average-risk adults at 45 years. I was older than 45.

- As mentioned above, my doctor knew I wanted a colonoscopy, without which I would constantly wonder about the possibility of CRC.

In addition, he told me cancer of the tail of the pancreas could present with symptoms like mine. Therefore, he recommended a CT scan (of my abdomen and pelvis) to rule that out.

Investigations

Here comes the interesting bit: findings of the colonoscopy and CT scan of my abdomen and pelvis. I had both tests on the same day, i.e., February 20, 2018. My gastroenterologist told me the results on the same day too.

Colonoscopy

First, the colonoscopy.

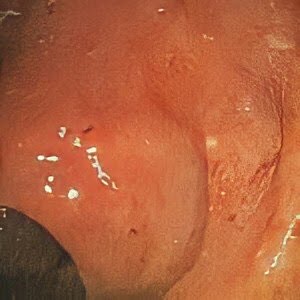

In the rectum, there was “circumferential erythematous mucosa with erosions and slough up to 6 centimeters from the anal verge” on colonoscopy. In layperson’s terms, this finding showed inflammation of the inside lining of my rectum, also known as “proctitis.”

The inflammation was at the bottom part of the rectum, just before the anus, and went all the way around the inside lining of the rectum (i.e., not localized to one or more spots). The rest of the colonoscopy, including the terminal ileum, was normal. The first photo on the right shows the multiple erythematous erosions on the mucosa of my rectum. These look like tiny red dots in the image.

In the next photo, you can see a thick layer of slough just next to the left edge of the image. There was presumably a lot more slough removed as part of the procedure. (If it wasn’t, we wouldn’t have been able to see what was underneath, would we?)

The photo on the right shows the inside of a normal rectum for comparison. I hope my rectum will look like this on my next colonoscopy!

Addendum: My colonoscopy on July 15, 2020, was normal.

Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography of the Abdomen and Pelvis

Next, the CT scan of my abdomen and pelvis.

The post-contrast images below are only a selection of all taken, focusing on the part between the level just below the mid-rectum to the anus.

The radiologist who reviewed the CT scan suspected “mucosal thickening in the lower rectum” and suggested a colonoscopy. (He didn’t know I had already undergone the procedure before the CT scan.)

Histopathology

I received the histopathological report three days after my colonoscopy. It confirmed acute proctitis. The reporting histopathologist believed the “overall features are in favour of an infectious-type proctitis rather than ulcerative proctitis.”

Response to Initial Treatment

Though the clinical history and colonoscopic findings, on the whole, were most suggestive of UC, my gastroenterologist based the initial treatment on the histopathology report. (When I questioned why I would have an infection down there, my doc said my travel history could have been a factor.) I received a two-week course of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole and a 3-day course of albendazole.

To be sure, I never believed my gastrointestinal symptoms were due to an active infection, but I took the antibiotics and antihelmintic regardless. If the antibiotics and antihelmintic could eliminate my symptoms, that would have been a fantastic result.

How did I go? In a word: terrible.

Over the next 14 days, my symptoms steadily worsened, despite me taking those meds religiously. Even after a few days, as my diarrhea, pus and mucus on the stools, and abdominal pain worsened, I knew the thing in my rear end was not due to a bacterial or tapeworm infection. Nevertheless, I soldiered on with the entire 14-day course of antibiotic treatment, if not for anything else, to prove a point (i.e., it wasn’t an infectious cause). I called the doctor’s clinic on the 13th day to make an appointment to see him on the last day of the course of antibiotics. By then, my symptoms were quite severe, almost intolerable.

Plan B: Mesalazine to Treat Presumed Ulcerative Colitis

I expected my gastroenterologist to tell me I needed another colonoscopy for more biopsies to be taken and sent for histopathological examination. But he took a more direct approach, which I thought was far more practical: a trial of mesalazine, also known as mesalamine or 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), in the form of Salofalk 500 mg tablets, one tablet three times daily. This dosage was lower than the intended dosage of Salofalk 1000 mg three times daily. My gastroenterologist was a little cautious because of my expressed concern over the drug (5-aminosalicylic acid, 5-ASA) being similar, in name and structure, to aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid, ASA), to which I am highly allergic. He reassured me that mesalazine was safe for me. My mesalazine dosage was increased to a more standard one – 1000 mg three times daily, i.e., 3 grams per day – a few days later.

In addition, I was prescribed a Salofalk suppository 500 mg, one to be taken at bedtime. I took the suppositories for about two weeks.

The results? Magic.

I expected the drug to show some effect in perhaps 2–3 weeks.

However, in my case, I noticed a remarkable boost in energy and a renewed sense of well-being after only three doses (about 24 hours)! I could confidently say I had not felt that good for over two decades. I’m sure it was not a placebo effect. However, I still haven’t figured out exactly how this occurred – I guess the drug, through its anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, reduced the production of systemic inflammatory mediators or blunted their effects.

All the other symptoms I believed were due to UC also improved over the ensuing days and weeks. Mesalazine was a game-changer, just as tegaserod (brand name: Zelmac) was for my gastroparesis 12 years earlier.

I’ve been taking mesalazine since March 2018, and my UC symptoms have not recurred. So we have achieved at least two goals of drug treatment: (i) induction of remission, and (ii) maintenance of remission.

I was due for a follow-up colonoscopy last month, i.e., approximately two years after first starting mesalazine. But the hospital postponed the procedure for three months. A limited supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) forced the hospital to cancel all elective cases, including mine. The lack of supply of PPE in the hospital was mainly because of US export restrictions on five categories of PPE in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These restrictions are ongoing.

The Diagnosis of Ulcerative Colitis

Ideally, to confirm the diagnosis of UC, the biopsy specimens of my rectal mucosa would have shown architectural and cellular changes typical of UC under the microscope. However, they saw only lymphoplasmacytosis, an inflammatory change often seen in UC. The lack of histopathological confirmation remains a contentious point for some people (doctors) I’ve told my UC diagnosis. To them, one can only make a UC diagnosis if a histopathology report backs it up.

There are at least three key points that support the diagnosis of UC:

- There is no viable alternative explanation for the distal rectal proctitis suggested in the history, e.g., infection, homosexual activity, radiation, etc.

- The trial of antibiotics and antihelmintic yielded zero beneficial effect. Therefore, an alternative diagnosis to UC (bacterial or tapeworm infection) became less likely.

- Excellent response to mesalazine. The only indication for mesalazine is in the treatment of UC. Based on the literature, this drug is not approved for treating any other bowel condition, though some people diagnosed with Crohn’s disease are also prescribed mesalazine. I’ve checked this with my gastroenterologist and others. In short, mesalazine should not have any clinical effect on any disease except inflammatory bowel disease, i.e., UC or Crohn’s disease.

IBS, which was diagnosed shortly after, also complicated making the UC diagnosis. More on the latter in a separate post.

The disease appeared to be confined to the distal rectum.

There were no apparent triggers precipitating the onset of the disease – I’m a lifetime non-smoker. I never take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because I’m allergic to them. I did not display any symptoms that suggested enteric infection.

Fix the Problem

Making a diagnosis is a means to an end; a diagnosis guides further management of the patient’s problem. It shouldn’t be the goal; it’s just a necessary step towards addressing the patient’s issues.

I encounter a similar situation in my consulting work. All my clients have a problem they want me to help fix. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t reach out to me. Solving their problem usually calls for knowledge, skills, intuition, and judgment – all of which are influenced by length, type, and quality of experience. Sticking to scientific principles and practices, or at least practices regarded as conventional by industry standards, is the most prudent course of action in most situations. However, sometimes one has to do something that knowingly deviates from standard practice. For example, in rare instances, I might (over)simplify an interpretation of an accreditation standard so that the client will accept the changes I propose. It might not be 100% accurate to the purists or my CPHQ students, but simplification might be pragmatic and necessary to solve the client’s problem (accreditation, in this example).

Back to my diagnosis. After the presumptive diagnosis of UC and specific treatment for this disease, my symptoms improved quickly, and I could function relatively normally soon after:

- No more (unpredictable) episodes of diarrhea.

- No more rectal bleeding, pus, or mucus.

- Stool caliber returned to normal.

- No more rectal pain.

- Overall energy level considerably improved.

- Exercise tolerance much improved, especially after some training. As an illustration, I can now row for 70 consecutive minutes (holding a stroke rate of 18 strokes per minute and decent split time of 2:10/500m throughout), run 10 kilometers, or ride 30+ kilometers and still have leftover gas in the tank afterward.

- Very little back pain or stiffness (not delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which I experience regularly).

- No more episodes of breathlessness and wheezing.

Problem solved for now.