My COVID-19 Vaccination Was Marred by Non-compliance With the Clinical Guidelines

Failure to carry out an administrative protocol to manage persons with known allergies led to a 47-day delay in my COVID-19 vaccination. In addition, my initial COVID-19 vaccination series saw a few lapses in compliance with the prescribed clinical guidelines, which fortunately did not lead to adverse sequelae.

I got my second shot of the Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2, Comirnaty®, or Tozinameran) vaccine on November 17, 2021. Therefore, I was “fully vaccinated” two weeks later, i.e., from December 1, 2021.

While considering whether I should take a booster jab, for which I will soon be eligible, I thought I would describe the side effects I experienced from my initial COVID-19 vaccination series to lend context to an otherwise moot question.

However, while researching the reported side effects of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, Google led me to the clinical guidelines on COVID-19 vaccination in Malaysia. I was not aware of these guidelines earlier.

The Ministry of Health of Malaysia has published four editions of these guidelines, the last one in October 2021. However, the third edition, published in July 2021, applied to me because my initial vaccination appointment was in September 2021.

Upon reading the clinical guidelines, I realized they were not strictly followed in my COVID-19 vaccination and might have inadvertently opened a can of worms.

In the first part of this blog post, I will outline the chronology of events that led to a delay of about six and a half weeks for my COVID-19 vaccination.

In the second part of this post, I will discuss how my vaccination did not follow the recommended guidelines and postulate why those instances of non-compliance occurred.

National COVID-19 Immunization Program

Below, I summarize the vaccine rollout in Malaysia.

Phase 1

The country took delivery of its first batch of COVID-19 vaccines in the last week of February 2021. Initial supplies were prioritized for healthcare workers and frontline staff – this was called Phase 1 of the “National COVID-19 Immunisation Programme” (NIP).

Phase 2

Phase 2 of the NIP targeted the following groups:

- Persons aged 60 and above

- Persons with chronic diseases such as heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure

- Persons with disabilities, i.e., those registered under the “Persons With Disabilities” (PWD), known locally as “Orang Kurang Upaya” (OKU), program

This phase started on April 17, 2021.

Phase 3

Phase 3 of the NIP covered adults below age 60.

My work did not involve direct patient care, and I had done my best to avoid exposure to persons infected or at high risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Therefore, I was not eligible for COVID-19 vaccination under NIP until Phase 3.

After a month’s delay, this phase officially began on June 21, 2021.

Registration for COVID-19 Vaccination

In March, people over 18 could register to receive the vaccine under the NIP, some three months before Phase 3 began.

But I held off registering for vaccination for a few reasons:

- The medium-term safety profile of all the vaccines which had received conditional registration approval by Malaysia’s Drug Control Authority (DCA) was unclear.

- I conducted most of my work online, limiting my COVID-19 exposure risk.

- I had a series of training sessions to deliver over Zoom, and I didn’t want to risk any vaccine side-effect impairing my performance or, worse, preventing me from performing on the scheduled dates.

- I wanted to discuss the COVID-19 vaccination with my gastroenterologist when I saw him at my scheduled appointment on July 6.

By July 2021, the Delta variant had emerged as the predominant variant in the US and many other countries.

WHO’s “Science in 5” on COVID-19: Delta variant – July 5, 2021

Compared with earlier variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the Delta variant was more contagious, and infected individuals were more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to die because of their infection. In addition, different studies on the efficacy of vaccines against clinical COVID-19 had yielded similar results – the vaccines in these studies prevented severe disease and death in adults. As is still the case, the unvaccinated were particularly at risk of COVID-19 illness and, if infected, of poorer outcomes, including death.

In the meantime, there were anecdotal reports of adverse effects following COVID-19 vaccination, but such events were rare.

The risks of remaining unvaccinated being untenable and the probability of suffering a severe adverse effect from a COVID-19 vaccine low, I registered to join the queue for a COVID-19 vaccination through the MySejahtera mobile application on July 17, 2021.

Appointment For First COVID-19 Vaccine Dose on September 10, 2021

Two and a half weeks later, i.e., on September 5, the Ministry of Health notified me of my appointment for my first jab at a community-based COVID-19 vaccination center at Tapak Pesta. My appointment was on September 10 at 10.00 a.m.

Five days was short notice for me, but I cleared out my day for this event. I looked forward to getting vaccinated.

When I accepted my appointment, I declared my “history of severe allergy” in the MySejahtera app, referring to previous episodes of anaphylaxis after ingesting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). My last anaphylactic reaction occurred in May 2013, when I was in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

On September 10, I arrived at the vaccination center more than half an hour earlier than my appointment time and joined the long line of people waiting to get their shot. Everything seemed to go smoothly despite the long queue.

I completed a paper form, on which I again declared my history of a severe allergy to NSAIDs.

Pre-Vaccination Assessment

As part of the COVID-19 vaccination process, I underwent a medical assessment (called a “pre-vaccination assessment,” or PVA, in the clinical guidelines) by a young medical officer.

She was concerned about my history of anaphylactic reactions to NSAIDs. So, she spoke with her supervisor, presumably a senior doctor, about my case over the phone. She told me his advice was to postpone my vaccination and to refer me to one of only several (I cannot remember exactly how many) selected public hospitals in Penang.

I chose Penang Hospital, also known as Penang General Hospital, the main public hospital on the island and the closest option from my home.

I repeatedly asked the doctor if I could go to Penang Adventist Hospital (PAH), my preferred private hospital on the island, instead of Penang Hospital. My rationale, which I shared with the doctor, was that PAH was a COVID-19 vaccination center under the NIP. In addition, folks at the hospital were familiar with my medical problems and could deal with any emergency. She told me this was not an option and that I could only have my vaccination jabs at one of the public hospitals on the list she showed me.

I couldn’t see what she was entering into the laptop computer on the desk between us. Still, as she was typing, I noticed my appointment in the MySejahtera app on my phone had disappeared. There was no sign I had presented for my first shot but was unsuitable to have my injection at a community-based vaccination center; instead, it looked like I had registered for vaccination but did not receive an appointment.

In truth, I was given an appointment on September 10, presented for it, and In reality, I received an appointment on September 10 and presented for it but did not get my vaccine injection over concerns about the possibility of a severe allergic reaction. The doctor told me I would receive an appointment at Penang Hospital on the MySejahtera app “very soon.”

Delay in First Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine

As it turned out, I would not get another vaccination appointment for over six weeks, and even when I received one, it was not done by conventional means. It required a considerable amount of effort and telephone calls on my part to get an appointment.

After September 10, I checked the MySejahtera app on my phone every day, sometimes a few times a day. But nothing changed. I could only see a record that I had registered for the COVID-19 vaccination on July 17.

By mid-October, I was becoming anxious that I was still unvaccinated. Besides being unprotected against COVID-19, I could not enter some places because I was unvaccinated, e.g., my local bicycle shop (being barred from entering my LBS was an enormous problem) and restaurants.

Further, on October 16, the local newspapers quoted the Health Minister saying, “Sorry to say, we will make life very difficult for you if you’re not vaccinated by choice.”

The issue for me was that I wanted to be vaccinated through the national vaccination program but had not received a replacement appointment, even though the doctor at Tapak Pesta told me I would get one.

Some weeks, I felt less nervous because I had scheduled work, either meetings or training sessions online. I would have preferred not to receive an appointment at short notice during such weeks as it would have inconvenienced many people.

However, as the weeks passed, I couldn’t help wondering if the system had lost me.

In a desperate attempt to get vaccinated, I contacted PAH to see if they could arrange for the NIP system to give me an appointment there, but that was not possible.

I also filled out a Google Form set up by the Penang State Government for persons registered for COVID-19 vaccination but who had not yet received their appointment on October 16. In the form, I gave details about my first appointment on September 10. They took no apparent action in response to the form I submitted.

My son’s appointment for his COVID-19 vaccine dose at the Tapak Pesta vaccination center, the same one where I was supposed to receive my first dose on October 22, provided an opportunity to get some answers. Unfortunately, the staff could neither explain why I had not received a replacement appointment nor rectify the problem. Instead, they suggested I call Penang Hospital.

I had to work on October 22 (Friday) and October 25 (Monday), but I called Penang Hospital on October 26.

The nurse who took my call explained that, because I was not a patient of The nurse who took my call explained that, because I was not a patient of Penang Hospital, I would not have been eligible for COVID-19 vaccination at Penang Hospital and, therefore, would not have received an appointment there. This information was contrary to what the doctor at the Tapak Pesta vaccination center told me on September 10.

To be vaccinated under the NIP, I would first have to present at the Health Clinic in my suburb, where a doctor would assess me. If the doctor considered me eligible for vaccination, they would administer the vaccine at the health clinic or a public hospital.

If the doctor deemed me medically unfit to receive a vaccine, they would give me a COVID-19 vaccination exemption certificate.

Going to the Health Clinic, which is only 850 meters from my home or an 11-minute walk according to Google Maps, did not appeal to me. Given my history of anaphylaxis and having seen the clinic (albeit from the passing road), I didn’t think it was appropriate for me to receive my vaccination there. Admittedly, my experience at Tapak Pesta contributed significantly to a lack of confidence in the medical staff at the clinic and a trust deficit in the public system.

Therefore, I asked the same person if I could go to my usual private hospital, operating as a COVID-19 vaccination center under the NIP, instead of the Health Clinic. Her reply was, “You can try.”

And try I did. I immediately telephoned the person coordinating the COVID-19 vaccination center at PAH, who was a friend (CML) with whom I had worked in the past. I told her everything I had gone through (as above), including what the nurse at Penang Hospital had told me over the phone.I immediately telephoned the person coordinating the COVID-19 vaccination center at PAH, a friend (CML) I had worked with in the past.And try I did. I immediately telephoned the person coordinating the COVID-19 vaccination center at PAH, who was a friend (CML) with whom I had worked in the past. I told her everything I had gone through, including what the nurse at Penang Hospital had said to me over the phone.

CML informed me that her center was no longer giving first shots of the COVID-19 vaccine (either Pfizer-BioNTech or Sinovac CoronaVac®, it didn’t matter). They were only administering the second vaccine doses to those who had previously received their first dose of the vaccine at the center. In addition, the hospital was closing down its operation as a COVID-19 vaccination center the following week.

CML said she could refer me to another private hospital, Lam Wah Ee Hospital (LWEH), which was still giving first doses. She couldn’t tell me if I qualified for COVID-19 vaccination – I had to be assessed by the medical staff there to find out.

So, I accepted the opportunity to be assessed for vaccination at LWEH the following morning, i.e., October 27.

COVID-19 Vaccination at Lam Wah Ee Hospital

When I arrived at the LWEH COVID-19 Vaccination Center, I learned CML had given the coordinator the relevant identification and demographic information about me, as she said she would.

A junior doctor assessed me and discussed my case with a consultant physician at the hospital. The decision was that I could have my vaccine shot that morning on the condition I agreed to pay for costs related to any emergency care rendered, e.g., intubation and ventilation, emergency drugs, ICU admission, etc. I thought it was a fair offer and took it.

While at the center, I saw only a few people – less than 20 – present for their vaccine jab. The trough in workload and the fact that the center had more than adequate staffing meant that I received much attention.

They took me to a resuscitation room and continuously monitored my oxygen saturation, pulse rate, and blood pressure. Two nurses observed me throughout my time in the room, which was well over an hour.

I was a little hypertensive (who could blame me?) with a systolic blood pressure of around 165 mmHg, but another nurse came into the room to administer the vaccine when it settled down. They gave me the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Fortunately, I had no immediate reaction to the vaccine.

The medical officer initially ordered observation for 60 minutes after the injection. She reviewed me after 45 minutes and felt at that time they had observed me for long enough. Thence they discharged me.

From the time I presented at the hospital’s front entrance to when they discharged me, the staff performed the entire process professionally and with compassion.

I returned three weeks later, on November 17, for my second dose of the vaccine. There were many more people in the queue on this occasion because, as I understood it, the authorities had given them (mostly elderly folk) appointments to receive their booster shots.

They gave me my second vaccine dose like that to any other person in the queue that day, with far less fanfare than the first injection.

The staff “observed” me in a specific area of the center and, after 15 minutes, told me I could go home. I hung around for another 15 minutes to be sure nothing untoward happened. When I was sure I would not react to the vaccine dose, I headed home, feeling happy I had finally completed my initial COVID-19 vaccination series.

Why There Was a Delay in My COVID-19 Vaccination

Although I remained in the NIP’s system, it might have been weeks or months before the system flagged me as a person still awaiting an appointment. It might not have identified me as requiring special precautions, and I might have got an appointment at a vaccination center not located in a hospital. If this were the case, my appointment would have been no different from my first appointment at Tapak Pesta.

According to the third edition of the Malaysian Health Ministry’s clinical guidelines on COVID-19 vaccination, the doctor was responsible for conducting the “pre-vaccination assessment” (PVA) and determining if I could receive a COVID-19 vaccine and when and where I should receive it.

Pre-vaccination assessment is an assessment conducted preferably by the treating doctor (i.e. medical officer or clinical specialist) to determine the suitability of individual to receive vaccine, timing to receive vaccine and suitable facility for the individual to receive vaccination (i.e hospital or other vaccination centre). The patient can also be assessed by the doctor on duty at the vaccination centre (PPV) according to the suitability to do so. For example, patients with history of allergic reaction may not be under regular follow up.

Clinical Guidelines on COVID-19 Vaccination in Malaysia, Third Edition, Page 29.

She did the right thing by consulting a senior physician.

However, where she erred was telling me the system behind the MySejahtera app would provide me with another appointment.

She should have been aware of the clinical guidelines on COVID-19 vaccination:

If the patient can receive vaccination, the doctor needs to decide whether he/she can receive vaccination in the hospital or at any Vaccination Centre in the community. The doctor needs to document result of PVA on the “Slip “Penilaian Kesesuaian Menerima Vaksin COVID-19 Bagi Pesakit Dengan Masalah Kesihatan Tertentu” (Refer example below).

Not all patients who fall into one of the 3 groups above need to be vaccinated in hospital-based vaccination center (SPPV). Some may still be suitable for vaccination at the community PPV (eg: PPV Awam or Komuniti) with appropriate observations post vaccination. For those who need to be vaccinated in the hospital, the doctor filling up the PVA form will need to make the necessary arrangements for them to be vaccinated in the hospitals where they are being followed up or at any other SPPV. This can be done by contacting the relevant SPPV, District Health Office of SPPV State Coordinator.

Clinical Guidelines on COVID-19 Vaccination in Malaysia, Third Edition, Page 29.

The guidelines include an example of a PVA form.

I also needn’t have had my COVID-19 vaccine jabs at a public hospital.

Suppose I was eligible for COVID-19 vaccination in a hospital. In that case, I could have had it at PAH, which served as a “hospital-based vaccination center (SPPV)” and which fell into the category of “hospitals where they are being followed up or at any other SPPV.”

Whichever hospital we had agreed on, she had the responsibility of filling up the PVA form and making the “necessary arrangements” for me to be vaccinated there – she had to do this by contacting the “relevant SPPV, District Health Office of (sic) SPPV State Coordinator.” The doctor only spoke with a senior physician and not to anyone else over the phone. She did not make the arrangements to have my COVID-19 vaccination at any hospital. If she had arranged my appointment with a responsible person at an SPPV, she would have been able to tell me the details, e.g., date and time, on the spot. I needn’t have waited for any notification through the MySejahtera app.

Alternatively, the doctor could have asked an administrative staff member at Tapak Pesta to make the phone call (or calls) to arrange an appointment for me. If they had made my appointment on September 10, I would not have waited 47 days for my first vaccine dose.

The requirement to arrange the person’s vaccination appointment at a hospital by the doctor who conducted the PVA was one of several changes made in the third edition of the guidelines; the second edition did not include this requirement. Therefore, one can surmise that, between April and July 2021, a substantial number of patients required their vaccinations in a hospital setting but did not receive their appointments; mine was not an isolated case.

The NIP system required a human to make the arrangements; a machine could not automatically make appointments at hospital-based vaccination centers. The authorities probably decided that the best person to make these arrangements, which involved making at least one telephone call to the relevant hospital (SPPV), District Health Office, or SPPV State Coordinator, was the doctor who conducted the pre-vaccination assessment.

Other Lapses in Compliance With the Clinical Guidelines

I wish I could say the doctor’s failure to arrange my first vaccination shot at a hospital-based vaccination center by directly contacting the center directly was the only breach of protocol.

But I discovered two other manifestations of non-adherence to the clinical guidelines in my case. The first one was serious; the second was minor in comparison.

1. Selection of COVID-19 Vaccine

Because I was someone who had a history of severe allergy, they should have given me the Sinovac vaccine to me instead of the Pfizer-BioNTech one.

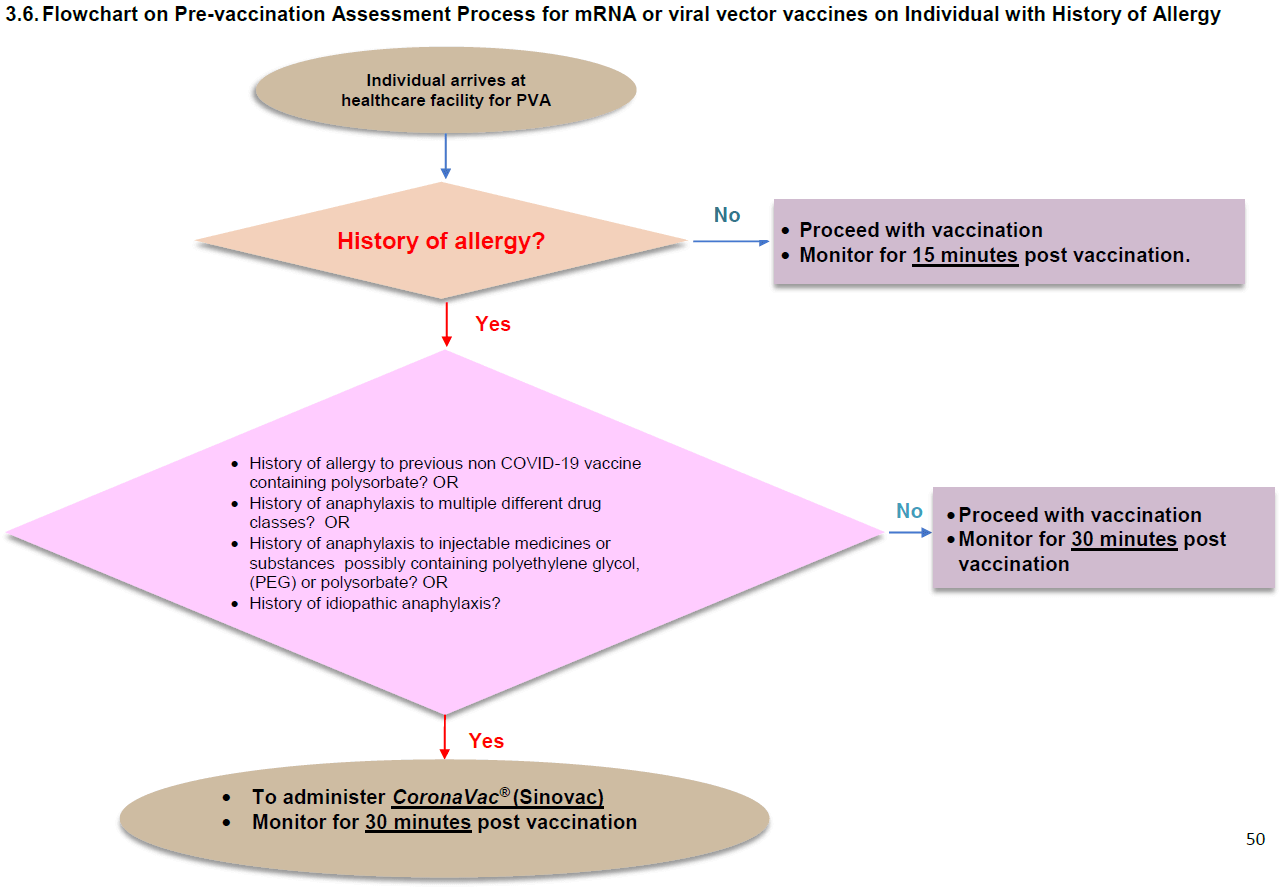

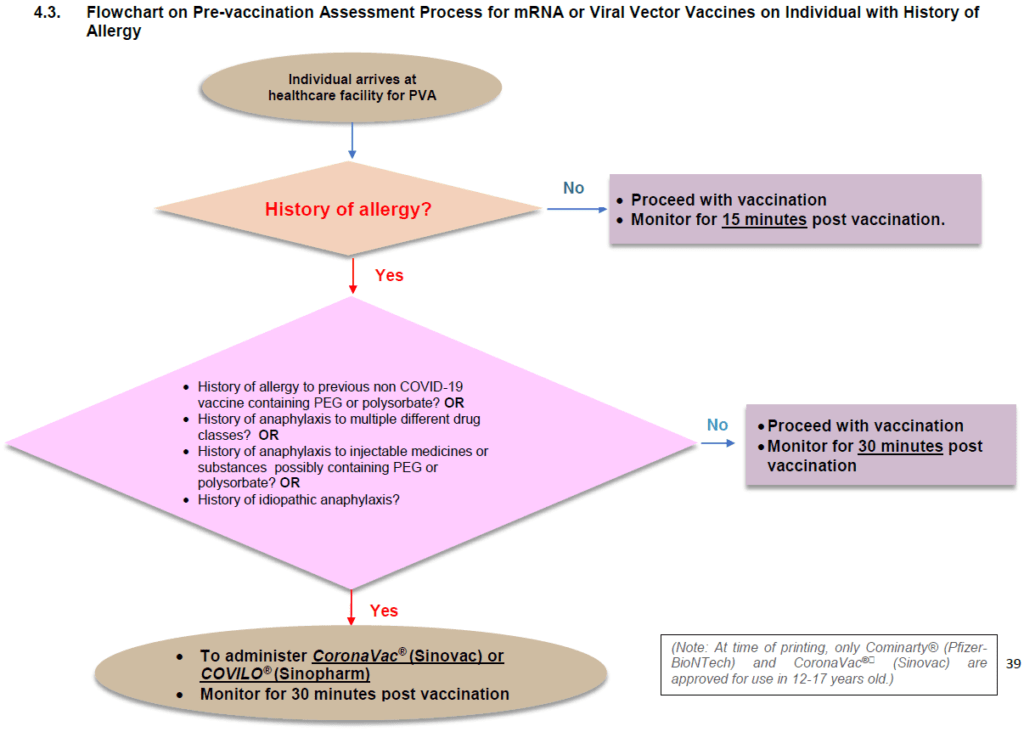

We can find the following flowchart on Page 50 of the third edition of the clinical guidelines.

In short, they gave me a vaccine not recommended by the clinical guidelines.

The guidelines do not include the rationale for recommending the Sinovac vaccine in persons with a history of allergy. However, I get the impression that the expert panel gave considerable thought to vaccine choice for this group. In the fourth and most current edition of the clinical guidelines, published in October 2021, they added the Sinopharm (COVILO®) vaccine as an alternative to the Sinovac one.

The guidelines continue to exclude the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, an mRNA vaccine, in favor of inactivated whole coronavirus COVID-19 vaccine. The Moderna Spikevax®, another mRNA vaccine, was (and remains) unavailable under the NIP.

The experts behind the guidelines might have had heightened concerns over possibly higher incidence of anaphylactic reactions with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, compared to non-mRNA vaccines.

I should count myself lucky that I did not develop an allergic reaction to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Had I known in September 2021 what I know now, I would have insisted on having the Sinovac vaccine to follow the guidelines and minimize the risk of an adverse event.

2. The Observation Period Following COVID-19 Vaccination

According to the guidelines, the hospital staff should have observed me for 30 minutes after each dose, not 60 minutes (as initially planned after my first shot) or 15 minutes (which happened followed my second shot).

On my first vaccination appointment, the plan to observe me for a more extended period than recommended was probably insignificant on that day. If the center was busy, they could have deployed the two nurses who attended to me in the resuscitation room to other tasks after half an hour.

On my second appointment, I was “observed” for 15 minutes – in reality, I was sitting in a waiting area with other persons who had also just had their jabs. However, nursing and medical staff were readily on hand if we unexpectedly developed symptoms. The fact I hung around the waiting area a little longer after being officially discharged mitigated the lapse in compliance with the guidelines.

Why Were the Clinical Guidelines on COVID-19 Vaccination Not Strictly Adhered To?

If staff had followed the clinical guidelines on COVID-19 vaccination:

- The doctor who did the pre-vaccination assessment on me at the Tapak Pesta vaccination center would have contacted the vaccination center at Penang Adventist Hospital to arrange an appointment for me there. She should have given me the appointment date and time on the spot.

- LWEH staff would have administered the Sinovac CoronaVac® vaccine, not the Pfizer-BioNTech Comirnaty® vaccine.

- The post-COVID-19 vaccination observation period would have been 30 minutes after each shot. Being observed for 45 minutes after my first dose was not an issue, but after my second dose, the observation period should not have been only 15 minutes.

Plausible explanations for these irregularities in compliance include:

- Lack of awareness of the guidelines

- Lack of supervision of compliance

- Lack of a (systematic) quality improvement program for the NIP

Lack of Awareness of the Guidelines

The junior doctors I encountered at Tapak Pesta and LWEH did not know the guidelines’ recommendation on the suitability of COVID-19 vaccination in persons with a history of NSAID-induced anaphylaxis. I am sure they would have told me so immediately if they did.

To their credit, both doctors deferred to more senior colleagues.

The two doctors being unaware of the guidelines is cause for concern..

Many people have known severe allergies. Based on the clinical guidelines, those with specific allergies should receive the Sinovac vaccine. (Not everyone with allergies should have the Sinovac vaccine.) We cannot expect average laypersons to know this; they rely on our healthcare providers to keep abreast of the Ministry of Health’s latest guidelines and follow them.

If a vaccination center does not have a stock of the Sinovac or Sinopharm vaccine, and a person meets the criteria for one of these vaccines, center staff should refer them to another center.

The Ministry of Health cannot afford to limit its communication of the clinical guidelines to an email with an attachment or a link to download the PDF file.

The NIP should incorporate ongoing education and training on the guidelines at different levels, especially for those in the front line, e.g., the doctors and nurses I met during my vaccinations.

In addition, we should give healthcare providers ample opportunity to seek clarification on points in the guidelines.

Lack of Supervision of Compliance

I suspect a systemic lack of supervision of compliance with the clinical guidelines.

I do not think it is appropriate to rely on individual healthcare providers and COVID-19 vaccination centers (both community- and hospital-based) to self-monitor compliance with the guidelines.

We should ideally implement systems and processes to monitor compliance with critical recommendations of the guidelines.

Processes within the Ministry of Health should generate compliance reports regularly and frequently.

We should give feedback to all levels, especially frontline staff, promptly.

Admittedly, compliance monitoring is not everyone’s cup of tea or everyone’s strongest suit. Monitoring compliance with the clinical guidelines on a scale as significant as the NIP requires an investment of immense amounts of human resources, coordination, and technical and communication skills.

Lack of a Quality Improvement Program

Supervision of compliance is necessary but insufficient. My experience with the NIP – not an isolated one – demonstrates we need quality improvement.

Here, I should distinguish between quality assurance, customary in the public setting, and quality improvement.

When we systematically determine whether our doctors and nurses did the “right” thing, e.g., follow the guidelines, we do quality assurance. Quality assurance implicitly assumes that we can have 100% compliance.

In theory, 100% compliance is achievable, but it is unrealistic.

Healthcare is a service industry – humans deliver it. We should neither demand nor expect perfection in healthcare.

I advocate quality improvement instead. Quality improvement implicitly accepts that our systems, processes, and personnel who execute them are imperfect.

The US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) summarizes quality improvement in the following way:

In health care, quality improvement (QI) is the framework we use to systematically improve the ways care is delivered to patients. Processes have characteristics that can be measured, analyzed, improved, and controlled. QI entails continuous efforts to achieve stable and predictable process results, that is, to reduce process variation and improve the outcomes of these processes both for patients and the health care organization and system. Achieving sustained QI requires commitment from the entire organization, particularly from top-level management. 1 1. Module 4. Approaches to Quality Improvement. Content last reviewed May 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/pf-handbook/mod4.html ×

The following table lists the differences between quality assurance and quality improvement.

| Quality Assurance | Quality Improvement |

|---|---|

| Individual focused | Systems focused |

| Perfection myth | Fallibility recognized |

| Solo practitioners | Teamwork |

| Peer review ignored | Peer review valued |

| Errors punished | Errors seen as opportunities for learning |

Quality improvement can and should be applied to the NIP. And let’s aim for excellence, not perfection.

Conclusions

There was a delay in my COVID-19 vaccination because the doctor tasked with performing the pre-vaccination assessment on me did not contact a hospital-based vaccination center to arrange my next appointment.

Acting on my initiative and with the help of a friend who was part of the NIP, I received my vaccination at a private hospital 47 days after my initial appointment. The delay would probably have been much longer if I had waited for the MySejahtera app to notify me of my next appointment. The appointment would have likely been at a community-based center under-equipped to provide the special precautions recommended for persons with a history of anaphylaxis.

I received the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine when the guidelines recommended the Sinovac one. Reports suggest a higher incidence of anaphylaxis after administering the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine than the Sinovac one. However, the events are still rare among recipients of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

The post-vaccination observation periods of 45 minutes (for my first dose) and 15 minutes (second dose) represented minor deviations from the clinical guidelines.

Reference(s)

- Module 4. Approaches to Quality Improvement. Content last reviewed May 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/pf-handbook/mod4.html ↩